Knowing your friends and coworkers’ hobbies can pay off. One of the guys I used to work with had told me about a Canadian Ross rifle that he’d inherited from his uncle. At the time, I really didn’t know much about the Ross rifles, other than that they had gotten a bad reputation in WW I for being too delicate for the muddy conditions of the trenches.

They were also known for being dangerous if you reassembled them incorrectly, which was apparently easy to do in field conditions. Despite that, I was still interested just because it was an unusual piece. I had always told him that if he ever wanted to get rid of it to let me know.

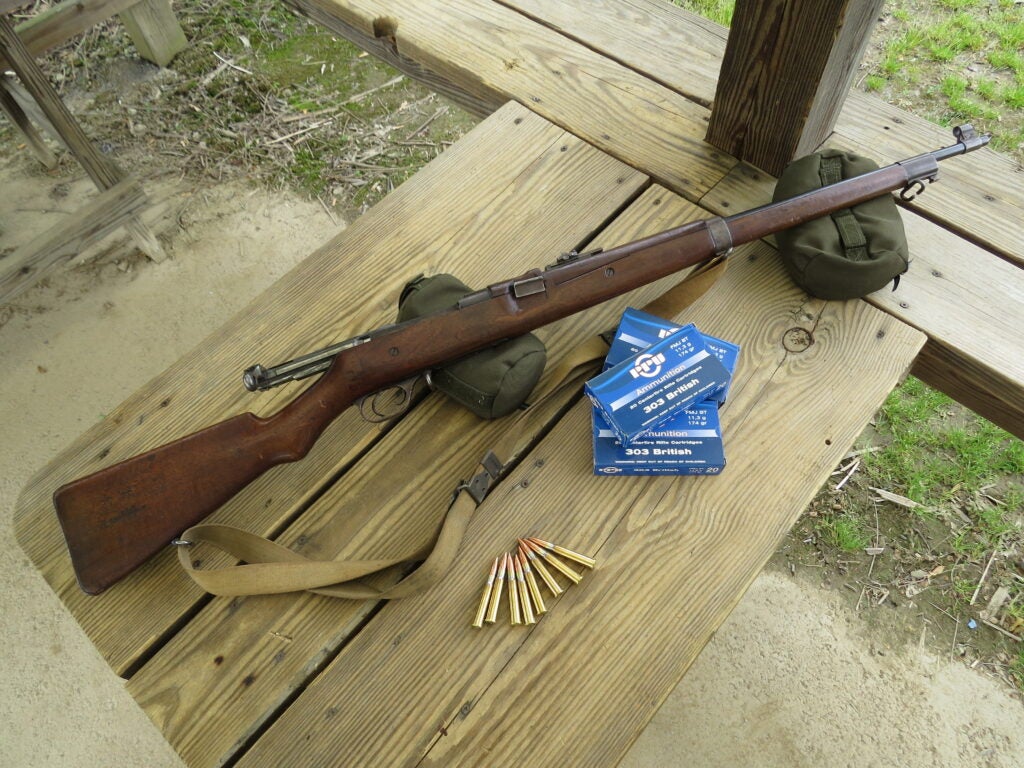

As things turned out just before Thanksgiving one year he told me he was going to bring the Ross in to work for me. I have to say I was taken by it at first sight. It was a rather elegant piece and obviously well made. It came up to the shoulder smartly and seemed well balanced. The action was stiff, but it had just come out of a decade-long storage quite recently.

When I asked what he wanted for the rifle he told me “Buy me lunch someday. I’d rather see the rifle go somewhere where it will be appreciated.” And appreciate it I did. I took the rifle home that night and immediately began to research it. That’s when I found out that there really hasn’t been a lot written on the Ross, at least that I could find online.

A Closer Look

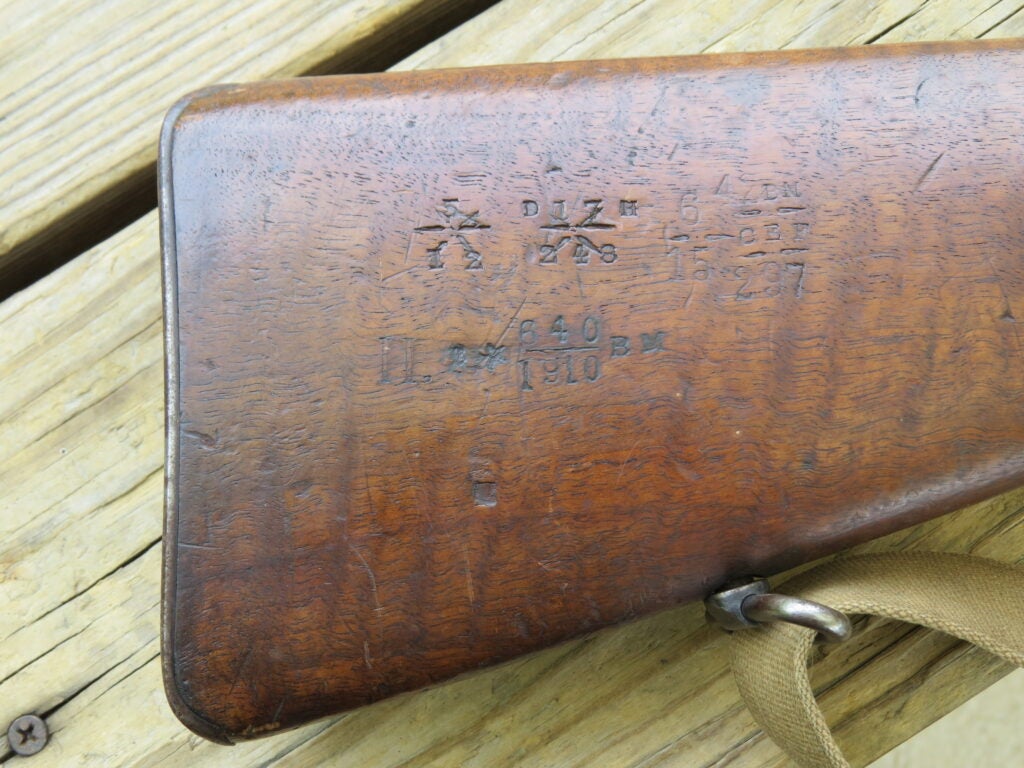

With a little bit of digging I found out a couple of interesting things about my new Ross. First my Ross was a MK II model, which apparently did not have the much maligned reassembly quirk that the later MK III’s did. There was no concern over whether this one was assembled correctly and would be safe to shoot. That was good to know.

A curious thing was that the rifle came with an American M1917 Kerr sling fitted. At first glance I just assumed Scott’s uncle put this on, but upon closer inspection of the rifle I found a U.S. stamp along with an American flaming ordinance bomb acceptance stamp on the stock. The mix of U.S. stamps and sling on the Canadian .303 rifle had me intrigued and caused me to dig deeper into the history of the rifle, and its connection to the U.S. military.

The Ross MK II

The Ross Mk II was developed in Canada during the early years of the 20th Century after a diplomatic spat kept the United Kingdom from licensing Canada to produce the Lee Enfield domestically. Sir Charles Ross, a Scottish inventor who was well-connected in Canadian political circles, stepped in to fill this void. He provided a domestically produced military rifle with his newly designed Ross rifle.

The rifle was a straight pull design chambered in the Commonwealth .303 British caliber, and fed from a 5 round internal box magazine. The initial Ross rifles were issued to the RCMP for field testing in 1902 which soon revealed a number of deficiencies. That resulted in a series of improvements being made and the designation of the Mk II rifle in 1905.

A series of further enhancements over the years resulted in the MK II* through MK II***** models being produced. Further design changes were made in coming years culminated with the MK III Ross being produced in 1910 which differed greatly from the original MK I and MK II models.

Tight Tolerance isn’t Always Good

When Canadian forces hit the trenches in World War I they rapidly found that the tight tolerances of the Ross rifles were not forgiving of the mud and debris common on the battlefield and weapon malfunctions were prevalent. This was also the time when the reassembly issues of the MK III became evident.

The combination of issues caused Canadian troops to abandon their Ross rifles at the earliest opportunity and acquire Lee Enfields from fallen British troops. The one bright note for the Ross was that it was an extremely accurate rifle. It did find success with Canadian snipers who presumably took better care of their weapons than the regular infantrymen. Regardless of this minor bright spot in the Ross’s military history the rifles were withdrawn from service in 1915 and replaced with the Lee Enfield No. 1 Mk III.

The US Connection

When I started looking into the U.S. connection for my Ross what I found was that one of the few sources of information on the Ross in U.S. service was the book “U.S. Infantry Weapons of the First World War” by Bruce N. Canfield. I ordered a copy and immediately turned to the section on the Ross when I got it. Thankfully, like all of Canfield’s work, the book is extremely well researched and has tidbits that you can’t seem to find elsewhere.

When you think of United States service rifles of World War One there’s a good chance that the Springfield Model 1903 springs to mind or perhaps the Model of 1917, more commonly known as the M1917 Enfield.

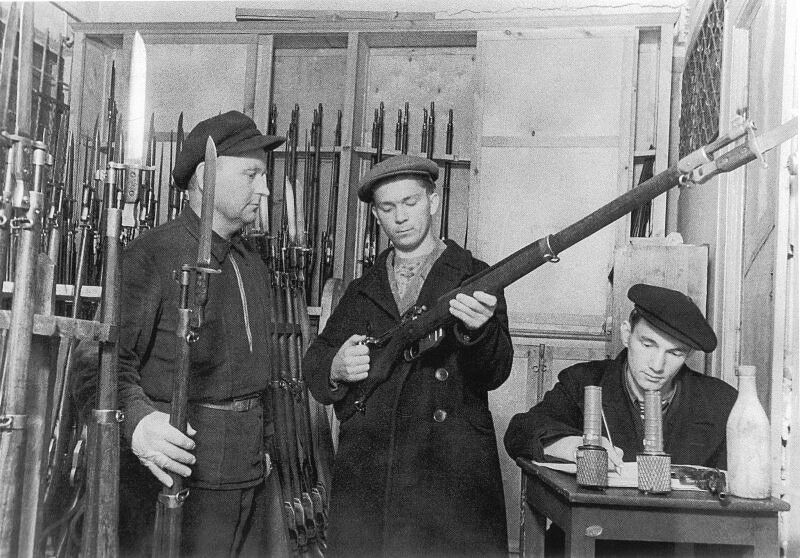

The United States entered WW I woefully unprepared however, and ended up issuing a hodgepodge of weaponry both on the battlefield in Europe and at home here in the U.S. for training purposes. One of the lesser known of those issue items was the Canadian Ross Mk II rifle.

After the Canadians withdrew the Ross from service they had an abundance of rifles in storage. That included 100,00 Mk I and Mk II rifles that they offered to the United States to use as training rifles. This would free up Springfield M1903’s and Model 1917 rifles for front line service.

The U.S ended up purchasing 20,000 MK II Ross rifles for training purposes, where they served alongside older M1898 Krag rifles and M1891 Mosin-Nagant rifles produced in the United States by Remington and Westinghouse. The Nagants had originally been produced for the Czarist government of Russia, but were left over stock that was never delivered following the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

According to Canfield, the United States paid $12.50 per Ross Mk II to the Canadian government, and that included a bayonet, scabbard, sling, and oil bottle. They also purchased over 4.5 million rounds of .303 ammunition, spare parts and manuals to go with the rifles. Half of the rifle purchases went to the state of New York to arm state guard units, while the rest were split up between training camps in Ohio and Massachusetts. When rifles were accepted into U.S service, they were stamped with the flaming ordinance bomb and the U.S. stamp followed by a serial number on the underside of the pistol grip.

The Ross Mk II was used stateside for training throughout WW I and then declared surplus at the war’s conclusion. The rifles were then offered for sale through the NRA of the princely sum of $5 each. The Ross didn’t prove to be popular, however, likely because of the tales of its performance with the Canadian forces during the war, and the price was later dropped to $3.50 each. Remaining stocks of Ross rifles were eventually returned to Canada in 1926. My buddy’s rifle was from one of the batches sold by the NRA after the war.

The Ross on the Range

I’m not a very good collector. It might be better to say that I’m an accumulator rather than a collector, in fact. I gather firearms that are of interest to me, particularly historical ones, but I’m not one to put them in the safe and forget about them.

To me, some of the allure of antique firearms is that they are an animate, interactive piece of history. They aren’t simply something you read about in a book but rather something you can see, touch, and experience firsthand. And that’s exactly what I did when I got my Ross.

I gave the Ross a good through cleaning, knocking out nearly a century’s worth of dust, grime, and old oil. Working with the rifle, it became apparent that the MK II was a very well-made. My example exhibited some dings from use and storage, but was in overall excellent condition. Fit and finish were very good, and it was obvious that a lot of attention to detail went into the design and execution of the weapon.

The bore proved to be shiny with good clean rifling once I ran some patches through it. The straight-pull action was actually quite slick and fast once it was cleaned and relubed. Three days later I was at the range of my local gun club with a couple of buddies and we were ready to make this Ross speak again after probably 90 years or so of sitting idle in a closet.

On our first trip to the range we took the Ross along with an Enfield No. 1 Mk III, the rifle which eventually replaced the Ross during WW I. Ammunition consisted of factory reloaded hunting soft points and some old military surplus .303 British. The Ross really does handle well.

I grew up shooting ’03 Springfields and I found that the Ross shouldered and pointed extremely well It was quite on par with what I was used to with my Springfields even though the Ross sported a longer 28 inch barrel. The rifle’s straight pull action was easy to work from the shoulder and the rate of fire capable of it was impressive.

We did find that you needed to work the bolt with some authority though as babying it would result in a jam. Extraction was quite vigorous throwing spent brass 10 feet or better to the right of the shooter.

The Ross Mk I and Mk II rifles did not use stripper clips and had to be loaded one round at a time. They use a Harris-controlled feed platform magazine that features an odd external lever that you can depress to take tension off the magazine spring and assist in loading. The slower reload was an obvious disadvantage compared to its contemporaries like the Lee Enfield, the Springfield M1903 and the Mauser Gewehr 98. On the range, however, it worked just fine, and was something of a novelty.

Handling the Ross side by side with the Enfield was interesting. My No.1 Mk III is an English BSA model manufactured in 1905, which made it the same vintage as the Ross. This particular rifle has arsenal markings which indicate it saw use in both WW I and WW II and, while still solid, is not in nearly as nice condition as the Ross.

What’s evident when shooting the rifles side by side is that Ross is a more elegant rifle. It shoulders faster, the grip provides a more comfortable wrist angle and it seems faster to get on target than the Enfield.

While we didn’t sit down and bench rest either war horse we did a good bit of offhand shooting with both rifles. I can see where the Ross would be popular with marksmen and snipers as it handles like a fine target rifle. Generally, our groups were about half the size of what we got from the Enfield despite having similar sighting systems. On a follow-up trip to the range, I ran 5 boxes of new-manufacture Prvi Partizan ammunition through the MK II. The feed was excellent, and the groups tightened up over the vintage ammunition that we had shot on our first range excursion.

From a pure range perspective, we preferred the Ross to the Enfield. However, when you factor in the Enfield’s 10-round capacity, ability to accept stripper clips, and enviable reputation for ruggedness, it becomes clear that the No. 1 Mk III is the superior battle rifle of the two.

Ross Wrap Up

Despite a rocky military service nearly 420,000 Ross rifles were manufactured between 1903 and 1915. They actually saw fairly widespread use during both WW I and WW II. In addition to its use by Canadian forces, and the U.S. Army for training purposes ,large numbers of Ross rifles also went to Great Britain during both wars.

More surprisingly, they also went to Russia during WW I, and then the Soviet Union during WW II under the Lend-Lease program. The Soviets converted some of their Ross rifle to use the Russian 7.62x54mm round during WW II to ease ammunition logistics on the Eastern Front. They continued to use those rifles for competition use after the war. They were even used for a short period by the Grand Ducal Guard of Luxembourg during 1945.

After running a few hundred rounds through the Ross and researching its history I have to say that the Ross Mk II is an intriguing rifle and a joy to shoot on the range. While not a particularly successful military rifle it has an interesting history to it, especially where it intersects with U.S. use during World War I.

While inferior to other contemporary designs it still fulfilled an important role by freeing up Springfield and Enfield rifles for front line combat for the US and filling on for service rifle shortfalls with other countries as well.

Ross MK II Specifications

- Caliber: .303 British

- Action: Straight pull bolt action

- Overall length: 51.97 inches

- Barrel length: 28 inches

- Weight: 8.59 pounds

- Magazine capacity: 5 rounds

- Year of introduction: 1905

Read the full article here

Leave a Reply